In Le v. Exeter Finan. Corp., No. 20-10377 (5th Cir. Mar. 5, 2021), in the course of reviewing summary judgment in a contract case, the Fifth Circuit notes that the “three-quarters of [the record] is troublingly sealed from the public” and condemns the “entrenched litigation practice[]” of “stipulated sealings.”

“In this case, the district court granted an agreed protective order, authorizing the sealing, in perpetuity, of any documents that the parties themselves labeled confidential. Result: nearly three-quarters of the record—3,202 of 4,391 pages—is hidden from public view, for no discernable reason other than both parties wanted it that way.”

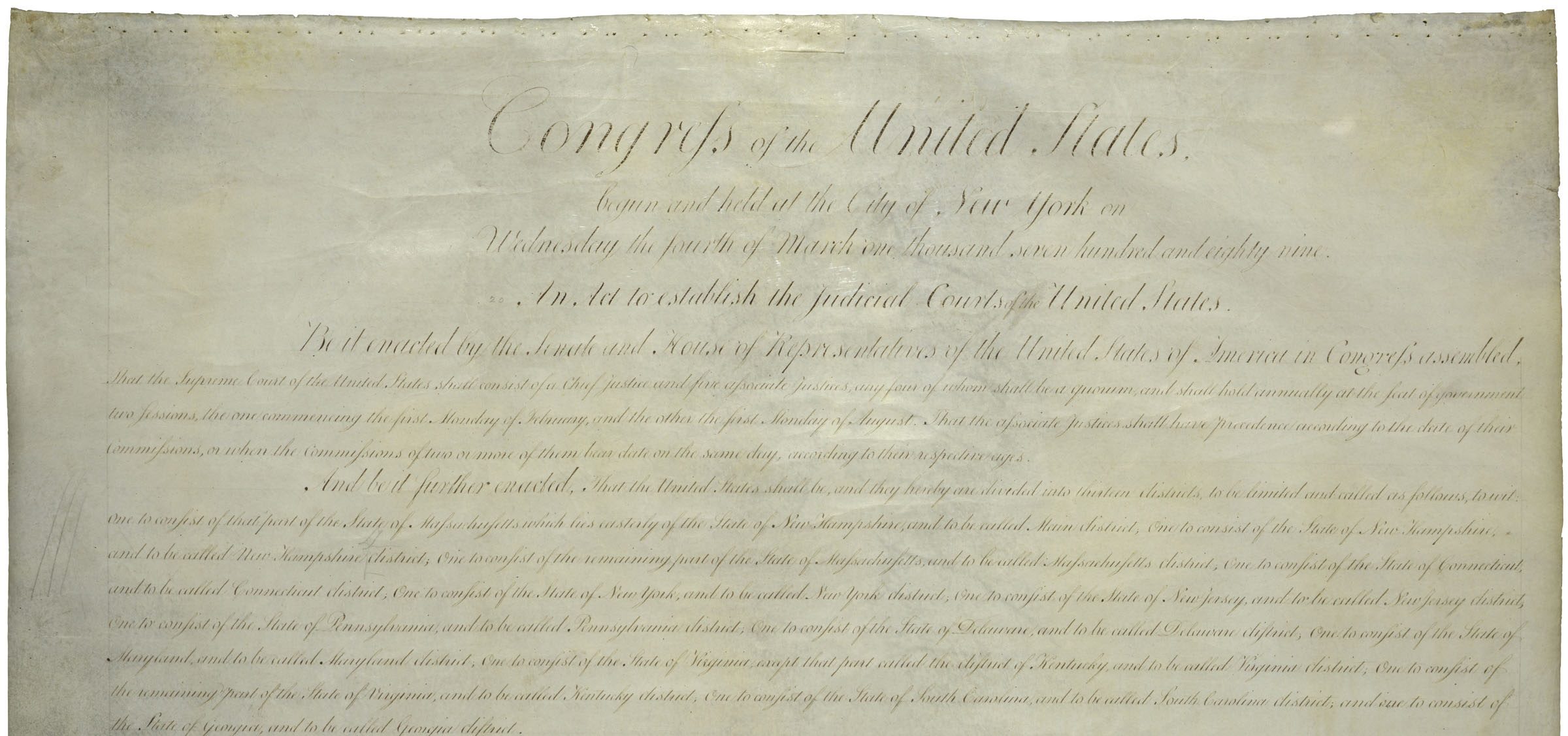

“The public deserves better. The presumption of openness is Law 101: ‘The public’s right of access to judicial records is a fundamental element of the rule of law.’ Openness is also Civics 101. The Constitution’s first three words make clear that ultimate sovereignty is wielded not by government but by the governed. And because ‘We the People’ are not meant to be bystanders, the default expectation is transparency—that what happens in the halls of government happens in public view. Americans cannot keep a watchful eye, either in capitols or in courthouses, if they are wearing blindfolds.”

While recognizing that “some cases involve sensitive information that, if disclosed, could endanger lives or threaten national security,” the panel finds that this was simply a “run-of-the-mill” case where the parties simply wanted to “keep things under wraps.” The oversealing in this case was problematic for three reasons. “First, courts are duty-bound to protect public access to judicial proceedings and records. Second, that duty is easy to overlook in stipulated sealings like this one, where the parties agree, the busy district court accommodates, and nobody is left in the courtroom to question whether the decision satisfied the substantive requirements. Third, this case is not unique, but consistent with the growing practice of parties agreeing to private discovery and presuming that whatever satisfies the lenient protective-order standard will necessarily satisfy the stringent sealing-order standard.”

The panel underscores the district judge’s role in keeping court files open. The judge “must undertake a case-by-case, ‘document-by-document,’ ‘line-by-line’ balancing of ‘the public’s common law right of access against the interests favoring nondisclosure.’ Sealings must be explained at ‘a level of detail that will allow for this Court’s review.’ And a court abuses its discretion if it ‘ma[kes] no mention of the presumption in favor of the public’s access to judicial records’ and fails to ‘articulate any reasons that would support sealing.’”

Here, the Court never reviewed the exhibits nor made the requite findings. Documents were filed under seal solely because they had been designated as confidential by the parties under the protective order. “In other words, the parties decided unilaterally what judicial records to keep secret, and their decision was permanent; once sealed, the records would stay that way …. Perhaps most disquieting, documents marked confidential provided the basis for summary judgment—a dispositive order adjudicating the litigants’ substantive rights (essentially a substitute for trial)—yet there was ‘no mention of the presumption in favor of the public’s access to judicial records.’”

The panel acknowledges that stipulated sealing has become the norm in civil litigation. Nevertheless, “we urge litigants and our judicial colleagues to zealously guard the public’s right of access to judicial records—their judicial records—so ‘that justice may not be done in a corner.’”